Review Overview

Accuracy - 7

Ease of use - 6

Usefulness - 7

6.7

A basic set of tools that can be used to do gender analysis during program design.

Gender is an important topic in international development / aid. Most donors ask you to explain how your project will address issues related to gender, and it can be difficult to know how to address that part of the proposal unless you’ve done a gender analysis.

Gender analysis is a method of exploring the different roles that women and men play in a community, the different opportunities and barriers they face, and the different levels of power they hold. A basic gender analysis should be done during the design of a program to understand the gender dynamics within a community. You can then use the results of the gender analysis to make sure the program benefits men and women equally.

There are many different tools available for doing gender analysis. Common ones include the Harvard analytical framework and the Moser gender analysis framework. There are also specific tools for gender analysis and gender analytics in health, food security, and even fisheries.

However, many of these tools are quite detailed and technical. They can be hard to apply to small projects – particularly if you’re not a gender specialist. The Gender Analysis Tools from the Vibrant Communities Gender and Poverty Project take the essence of all these complex frameworks and reduce them to some basic steps. The toolkit was created for poverty reduction programs, but it could work equally well on most other projects. It’s only 14 pages long (compared to hundreds of pages for some of the other frameworks), so even a busy program manager should have time to read it.

How does it work?

The toolkit starts with an introduction to gender analysis. It then takes you through a series of questions that need to be answered about men and women in the community. There are three types of questions:

- Questions about roles and activities (Who does what?)

- Questions about access and control (Who has what?)

- Questions about the influencing factors (Why?)

Here are some of the questions in the first set (Who does what?):

- What roles do men and women typically play in the community?

- Who works for pay?

- Who cares for children and covers other family work (‘reproductive work’)?

- How many hours a day are spent on home and family care?

- What number of hours are spent doing unpaid, underpaid, or undervalued work?

- Is there a family member involved in a community organization or volunteer work? Who? For how many hours a week?

The toolkit gives some suggestions for how to answer these questions using both traditional methods (e.g. surveys, mapping, formal interviews) and non-traditional methods (e.g. focus groups, informal conversations, walking tours). They give specific instructions for several activities you can run with groups of people to answer specific questions.

What is it like to use in practice?

To test the toolkit I tried to answer the questions and complete some of the activities for a project I am currently working on. The questions in the first two categories (who does what? who has what?) were easy to understand. We were able to think of ways to answer each question using both traditional and non-traditional methods, although it would have been nice if the toolkit included some sample survey questions to use.

The questions in the third category (Why?) were more challenging. Gender issues are very complex, and it was difficult to think of all the possible reasons why things are the way they are. It would have been helpful if the toolkit gave more detailed examples and activities to assist with this.

I was particularly impressed that the toolkit gave equal emphasis to both men and women. Gender analysis often focuses on the barriers and constraints that women face, without considering those that men might face. This can be a major oversight for some types of programs.

For example, I once reviewed a child health program that was running training sessions for “mother groups” during the middle of the day. Both the name of the sessions and the timing meant that men assumed the activity was only for women. This not only perpetuated the belief that women’s role was caring for children, but it also prevented men from learning more about their children’s health.

What do the results look like and how can they be used?

After completing the gender analysis, you should have answers to each of the questions in the toolkit. If you used a traditional method to answer the questions (e.g. a survey), then the answer might be in the form of a statistic (e.g. “In 73% of households only men work for pay”).

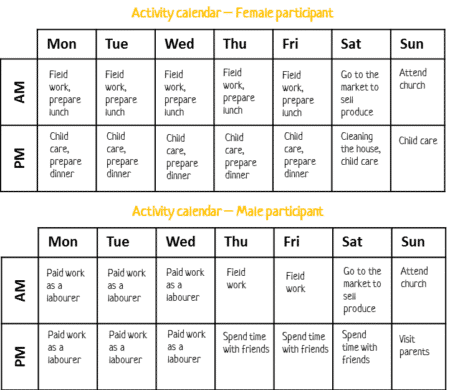

If you used non-traditional methods, then the answer might be in another form. For example, if you ran focus groups to complete the activity calendar exercise then the result might look something like this:

You can use these results to assess whether your program is accessible to both men and women. If the gender analysis shows that men are usually available on weekends, while women are usually available on weekday afternoons then you might change your schedule to allow both men and women to participate at different times.

The results can also be used to assess whether the program is likely to benefit men and women equally. In a micro-finance program the analysis might show that men own most of the small businesses, but their wives do most of the unpaid work managing the business day-to-day. In this case the program may inadvertently benefit men more, while creating more work for women, unless specific steps are taken to avoid this.

What are the limitations?

The Vibrant Communities toolkit is a very basic set of tools for completing gender analysis. It is suitable for small to medium sized projects, but may be too simple for large projects or high-level policy work.

It was also developed for poverty reduction and so it doesn’t address specific topics that might be relevant for other types of projects (e.g. health, environment, food security, etc.). In these cases it might be best to combine it with other gender analysis tools that are specific to a particular topic.

Finally, the toolkit says that you can answer the questions using traditional or non-traditional methods. In my experience I think it would be better to say traditional and non-traditional methods (if possible). Non-traditional methods are very good for identifying possible gender issues that exist in the community, but they can’t confirm how many people are actually affected.

To illustrate – I was recently involved in a series of focus group sessions in Malawi where community members said that many pregnant women chose not to deliver at the health centre because their husbands would not allow them to go. To us, this sounded very plausible and we proceeded to design a new intervention for men that would encourage them to change this practice.

However, after we did our baseline survey we discovered that less than 2% of the women who delivered at home said it was because their husband prevented them from going to the health centre. In reality, the main reason for delivering at home was distance and lack of transport. As a result we switched our focus from men’s attitudes to transport.

The bottom line

The Gender Analysis Tools from the Vibrant Communities Gender and Poverty Project are a basic set of tools that can be used to do gender analysis during program design.

The Vibrant Communities Gender Analysis Tools are useful when:

- You need to do a basic gender analysis for a small to medium sized project

- You want to know if your project will benefit men and women equally

- You don’t know what to write in the gender section of a proposal

The Vibrant Communities Gender Analysis Tools are NOT useful when:

- You need to do a gender analysis on a specific topic (e.g. health, food security, climate change)

- You have a large or complex program / policy (in this case it might be better to use one of the more detailed tools)

Photo by Jason Cipriani