Semi-structured interviews are a staple of international development programs. Unfortunately they are often done in a rush without proper planning and analysis. The result can be a pile of interview notes that don’t contain the information you need, or simply repeat the same points over and over without adding anything new. To avoid this scenario follow these steps for doing great semi-structured interviews.

This advice is for:

- Interviews of program stakeholders, such as participants, staff, community leaders, government officials, etc.

- Interviews used to collect information on people’s ideas, opinions, or experiences.

- Interviews done by program staff as part of an internal needs assessment or program evaluation.

This advice is NOT for:

- Academic research studies conducted by universities, PhD students, etc.

- Interviews done by external consultants or research firms as part of a complex needs assessment or program evaluation.

Use semi-structured interviews when appropriate

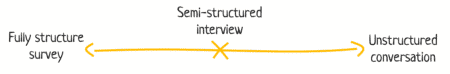

Semi-structured interviews sit halfway between a structured survey and an unstructured conversation.

Semi-structured interviews are particularly useful for collecting information on people’s ideas, opinions, or experiences. They are often used during needs assessment, program design or evaluation. Semi-structured interviews should not be used to collect numerical information, such as the number of households with a bed net, or the number of farmers using fertiliser. In that case a quantitative survey would be better.

Consider ethical issues

Although it might seem like you’re just sitting down to have a chat with some stakeholders, a semi-structured interview is actually a research tool and so you need to consider the ethical implications. You should always ask for informed consent and explain the purpose of the interview and how the information will be used. In some cases the consent could be done verbally, and in other cases you may need to have written consent.

You also need to consider who will be doing the interview (including if there is a translator), and whether they are suitable for the topic being discussed. In some cultures it may not be appropriate for men or women to discuss particular topics. It also wouldn’t be appropriate to have field staff interview participants about the effectiveness of the activities they run, as the participants may feel pressure to give positive answers.

Prepare an interview guide

By definition, a semi-structured interview needs to have some structure, although that structure should be flexible. This flexible structure is normally provided by an interview guide that lists the key questions for the interview. The interviewer is normally free to add questions or change the order if necessary. When preparing an interview guide:

Write the interview questions in the local language first

If you’re a native English speaker, it can be tempting to write the interview questions in English first and then translate them into the local language (either in advance or during the interview). As with survey questions this can lead to a whole range of misunderstandings and confusion that could make your interview results useless. Where possible write the questions in the local language first and then translate them into English or another language.

Include space for demographic information

It’s helpful to include some space at the start of the interview guide to record key demographic information about the interviewee. This could include their sex, age, position, location, and their name (unless the interview is confidential). This information will be helpful during the analysis and report writing later on.

Use open ended questions

The purpose of an interview is to understand people’s ideas, opinions and experiences. These are best captured using questions that don’t have a fixed set of answers, such as “What are your views on X?” or “How do you feel about Y?”. If you find yourself writing multiple choice questions then reconsider whether you should actually be doing a survey.

Provide a section for the interviewer’s observations and opinions

One of the most common problems with semi-structured interviews done by program staff is that the interviewer mixes in their personal opinions when they are taking notes. Sometimes it can be difficult to tell what the real opinion of the interviewee was compared to the interviewer. One of the best ways to prevent this is to provide a separate space at the end of the form where the interviewer can put their own subjective opinions (e.g. “the chief was present so I don’t think she gave accurate answers”, “I think the reason she said the activity wasn’t useful is because lunch wasn’t provided”).

Test the guide and train the interviewers

Follow the same steps for pre-testing and piloting a survey questionnaire to make sure your interview guide works in practice. Pre-testing can also be used as an opportunity for training the interviewers. It’s usually better to train them using real interviews, rather than just running through the questions together at the office.

Interview as many people as necessary to find out what you need to know

One of the most common questions asked about interviews is how big the sample size should be. There is no correct answer to this question because it depends on what you need to know.

One method that I often use is to choose a range of people with different backgrounds and positions (e.g. some poor, some rich, some old, some young, some men, some women, some community members, some community leaders, etc.). Then I keep interviewing people until I’m no longer getting any new information. When all the answers are the same as answers I’ve heard before I know it’s time to stop.

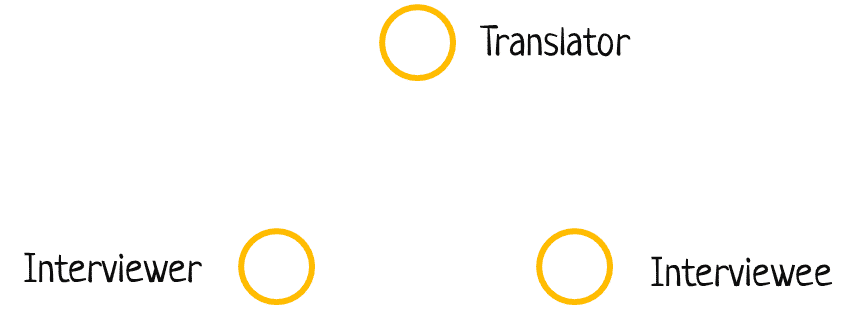

If you are using a translator, sit in a triangle

Conducting interviews through a translator can be difficult and time consuming, particularly when the translator is a member of staff and not a trained interpreter.

If you must use a translator then make sure you rehearse the key questions with them beforehand, as well as any follow-up questions you are likely to ask. They should have a copy of the interview guide written in the local language. When conducting the interview sit in a triangle shape so that all three of you can see each other easily.

Listen to the answers and ask follow-up questions

When you’re conducting an interview one of the most important skills is to listen to the interviewee’s answers closely. You can then use the answers to ask follow-up questions in order to get more useful information.

This can be one of the most difficult skills for field staff to learn, particularly if they are used to doing fully structured surveys where no creativity is required. It can be useful to include some suggested follow-up questions in the interview guide. The most common follow-up questions should become obvious during the pre-testing.

Record key quotes word-for-word

In an ideal world every interviewer would be equipped with a voice recorder to record the whole interview. The whole interview would then be transcribed in the original language before being analysed (possibly using computer software).

In reality, most programs don’t have enough funds to buy voice recorders and there isn’t enough time to transcribe whole interviews. Often the interviewer just takes hand written notes on the interview guide form. However, one of the dangers of this is that the original “voice” of the interviewee will be lost.

So even if the interviewer is handwriting notes during the interview, it’s still very important to try and write the key quotes word-for-word in the language they were said in.

Get multiple opinions on the translation

One of the reasons why it’s so important to record the key quotes in the language they were said is that there are often several different ways to translate them. Rather than having the interviewer do a quick translation on the spot, it’s better to bring the quotes back to the office where two or more people can debate the best way to translate it while preserving the original meaning.

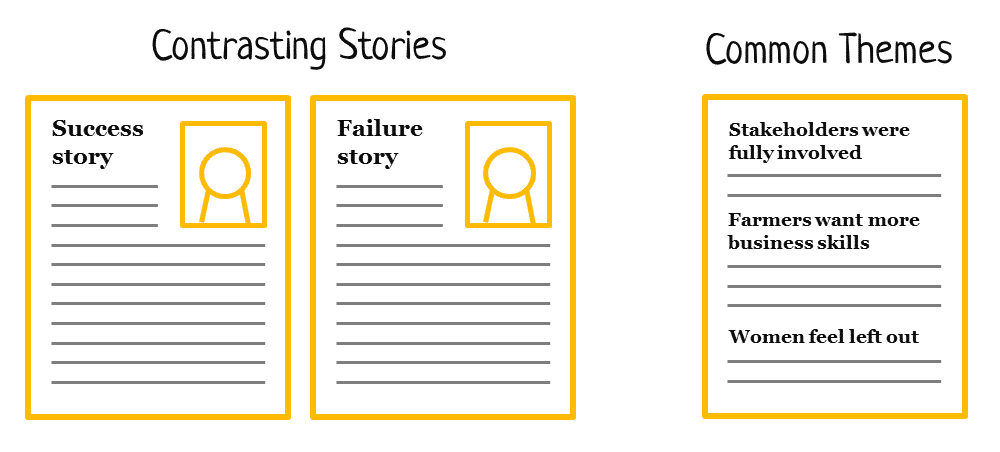

Use the results to write contrasting stories or identify common themes

In academic research, interviews are usually analysed using complicated sounding techniques like “coding” or “content analysis”. If you know how to do this that’s great (there’s no need for you to be reading this guide). If you don’t know how to do this then you’ve got a lot in common with a lot of people working in international development.

There are two basic ways to analyse and report interview data – you can use it to write stories or to identify common themes.

Writing stories is particularly useful when you’re doing an evaluation. Use the interviews to identify people who have different ideas about how successful the program was. For example, in a micro-enterprise program find one person whose business was very successful, one who had a moderately successful business, and one whose business failed. Then use the interviews to tell their individual stories, including direct quotes from them.

The alternative method is to have a group of people look at all the interviews to identify the common themes. A common theme is something that is said repeatedly by different interviewees. For example, in a training program many people might have said that the training sessions are too long. This would be a theme. Once you’ve identified all the themes you can describe them in your report.

Photo by International Rice Research Institute (IRRI)