Special thanks to Raizel Albano for suggesting this post, and for providing a case study on conducting research with indigenous communities in the Philippines.

If you’re planning to conduct any type of research (qualitative or quantitative), it is essential that you first get informed consent from the participants. If someone gives informed consent it means they voluntarily agree to participate in the research, with a full understanding of the expected risks and benefits. Historically, individuals often participated in research without knowing the risks involved and suffered as a result. This is why the informed consent process is so important.

Most people think of informed consent as being given by an individual participating in the study. However, there are actually multiple levels of consent that need to be considered, including at the governmental level, community level, and individual level. This guide gives an overview of how to approach informed consent at these levels.

This advice is for:

- Quantitative surveys such as feedback forms, needs assessments, baseline, and end-line surveys, etc.

- Qualitative research such as interviews, focus groups, etc.

This advice is NOT for:

- Clinical trials, biomedical research or medical practice where national regulations for informed consent normally apply.

- Research involving vulnerable populations where the individual participating may have a limited ability to consent (e.g. prisoners, children, people with intellectual disabilities).

Governmental Level

You should always get consent for any research or program from the relevant government department. For example, if you are doing a survey regarding health issues you should get consent from the Ministry of Health. If you are doing focus groups with teachers you should get consent from the Ministry of Education. It’s a good idea to get this consent in writing, or as part of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU).

If the purpose of your study is to conduct scientific research (i.e. it is not part of the monitoring / evaluation for a program), then you will also need to get approval from the national ethics committee. This normally involves completing a formal application that describes the purpose of your research, the methods, the benefits of the research, and the potential risk to participants. The WHO maintains a list of all national ethics committees and their contact details. National ethics committees often take months (or even years) to process applications, and you can’t proceed with any further steps until you have their approval. So make sure you start this process early. The committee may also request that you make changes to your methods before they will approve it.

If your study is for the monitoring or evaluation of a program (rather than for scientific research), then the question of whether you need ethics committee approval is more complex. For a full discussion see: Does my study need ethics committee approval? You can also do a quick assessment yourself using the ARECCI Ethics Screening Tool to see if your study is likely to need formal approval (although remember to also check against the relevant national regulations).

Community Level

Once you’ve got consent from the relevant government department (and the national ethics committee if necessary) you then need to get consent at the community level. This normally involves having a meeting with community elders or village chiefs, local government representatives (e.g. councillors or committee members), and other stakeholders (e.g. local health centre staff or teachers) to explain the purpose of the study, and the potential benefits and risks to the community and participants.

The community leaders might request changes to the methods, or may refuse to give approval for the study, in which case you should not proceed. If you do get consent from community leaders it’s a good idea to put it in writing in the local language and have all the community leaders sign or thumb print on the approval. You should also plan to come back at the end of the study and share your findings with them.

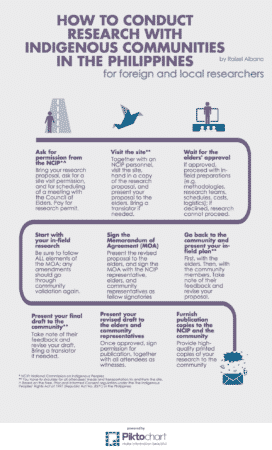

Case Study

The following diagram created by Raizel Albano shows the process for getting informed consent from in indigenous communities in the Philippines. This process is part of creating Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plans (ADSDPP) by World Friends Foundation, Inc.

Individual Level

The last level of consent you will need is from the individuals participating the the study. Informed consent by an individual involves three elements:

- information,

- comprehension, and

- voluntariness.

Information

The first step is to prepare an information sheet for participants that includes the following information as a minimum:

- An explanation of the purposes of the research, how long it will take, and the procedures to be followed.

- A description of any risks to the person participating (if relevant).

- A description of any expected benefits to the person participating, or to their community, as a result of participating.

- A statement describing whether the data will be anonymous or stored confidentially.

- A description of any reimbursement or gift that the participant will receive for participating (if relevant).

- Contact details for the person to get in touch with if they have questions or concerns regarding the research.

- A statement that participation is voluntary, that refusal to participate will involve no penalty, and that the subject may stop participating at any time.

Note: The national ethics committee may require additional information, so you should check their guidelines.

An example of an information sheet from a baseline survey for a health program:

Informed Consent Example

Hello. My name is _____________ and I am working with International Health Alliance.

We are conducting a survey about health issues in this area, and would very much appreciate your participation. This information will help us to design our program to improve the health of people in this community. The survey usually takes between 15 and 30 minutes to complete.

As part of the survey we will ask some questions about your household. Whatever information you provide will be kept strictly confidential, and will not be shared with anyone other than members of our survey team.

Participation in this survey is voluntary, and if you decide not to participate there won’t be any penalty. If you do decide to go ahead and we come to any question you don’t want to answer, just let me know and I will go on to the next question. You can also stop the survey at any time. However, we hope that you will participate in this survey since your views are important.

At this time do you want to ask me anything about the survey? If you have any questions or concerns in the future you can also call my manager, Christopher Waru, on 8754 8965 or visit our office in Bunda.

If you agree to participate in the survey can you please put your thumb print or signature below.

I, ____________, understand this information and agree to participate.

Thumb print / signature

Comprehension

It’s important that participants are able to understand the information they have been provided. The information sheet should be written in plain language and must be translated into the local language(s). Participants should be given time to ask any questions or clarify points before proceeding.

If the participant is not able to read then the information sheet should be read out to them verbally from a script written in the local language. It’s not a good idea to have bi-lingual staff translating the information sheet “on the fly” as they may translate it with a different meaning each time.

You can also illustrate the information sheet with pictures to help people understand its meaning (see example below).

An enumerator uses a poster to obtain informed consent for research conducted by ILRI in Morogoro, Tanzania (photo credit: ILRI/Tarni Cooper)

Voluntariness

Participation in the study must be voluntary, so it’s important to make sure the participant does not experience any pressure from others to participate.

This is an important consideration if you decide to reimburse participants for their time or provide a gift for participating. If the reimbursement or gift is too large then participants may feel under pressure to participate, which calls into question whether the consent was truly voluntary. As a general guide, any gift should be small enough that the individual would be able to purchase it for themselves, should they wish to.

For short interviews or focus groups it’s normally fine for participants to give consent verbally. However, if the topic is sensitive, you plan to quote people directly with their full name, or you are doing a quantitative survey, then it’s best to get written consent. If the participant is not able to write then a thumb print is a good alternative. Another option is to record the participant giving verbal consent using a voice recorder or video camera.

Photo by Pixabay