Fraud and corruption in international development projects are often cited as a reason to stop giving aid. The UNDP broadly defines fraud as any act (or omission) to obtain a financial or other benefit or to avoid an obligation. This differs slightly from corrupt practices, which the UNDP understands to be “…the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting, directly or indirectly, anything of value to influence improperly the actions of another party.”

While fraud and corruption are by no means limited to developing countries – just look at the expenses scandals in the UK and corporate corruption cases in the US – there are some unique aspects to working in developing countries that can make it more difficult to control.

To start with, a greater proportion of transactions in international development projects are done in cash because many local suppliers in the countries where activities are being carried out don’t accept cheque, credit card or bank transfer. Employees often handle cash, equipment and procurement contracts valued far higher than their salary (compared to employees in developed countries). Finally, program participants often have lower levels of education. This makes it more difficult for them to read receipts and other documents they may be signing, and to make complaints if they don’t receive services.

Preventing fraud and corruption is something that has to start on the ground, where the program is being implemented. So if you’re working directly on an international development program I encourage you to use these few simple tips to try to prevent it on your project.

Audit receipts at the supplier

According to a U4 report on corruption and fraud in international aid projects, “standard audits are not designed to detect fraud and seldom do.” This may come as a surprise to some people, but it’s true. In a standard external audit (the type required by most donors) the auditors will just sit in your office and check that every expense has a receipt and the necessary paperwork (quotes, invoices, proposals, etc). They won’t actually go outside the office to check if the receipts are real. This is true for big international audit firms and local firms alike.

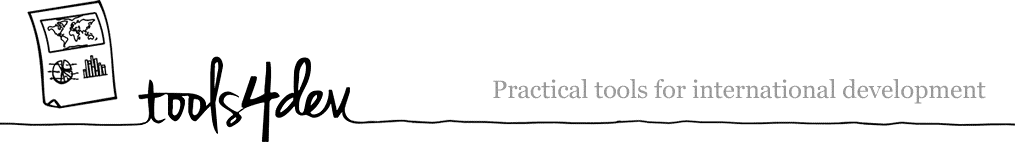

The photo below shows a receipt for a bag of cement – something which would be typical on any construction project:

This receipt would be accepted by most external auditors as valid. However, there are still ways in which the receipt could be used to hide fraud:

- Fake receipt: The company itself may be fake, or the person making the purchase may have created a fake receipt in order to keep the money. This can be caught by visiting the address on the receipt to verify if it is a real company, and checking their duplicate receipt book to make sure the receipt actually came from there.

- Altered receipt: It is possible that someone may have altered the receipt after receiving it from the supplier. For example, adding 0’s to the end. Comparing the original receipt with the duplicate at the supplier would detect this.

- Kickbacks: The employee purchasing the item and the supplier could have colluded to inflate the price, splitting the extra profits between them. This can be the most difficult type of fraud to detect because the original receipt and the duplicate will match. The only way to catch this is to do price checking, where you pretend to be from a different organisation and ask about the usual price of the goods or services. This can be done at the supplier in question, and also other suppliers for comparison (to make sure the most competitive supplier was selected).

Since regular audits are not designed to detect these types of fraud, it’s critical that you audit a random selection of receipts every month by visiting the supplier in person.

Download Receipt Audit template

Check that activities were actually implemented

Aid funds are used to implement project activities, so one way of stealing the funds is to fake the implementation of activities. This is often done by creating “ghost” beneficiaries who appear to receive per-diems or supplies (food, seeds, bed nets, etc) but never do. It can also be done by purchasing equipment and supplies that are then sold, or exchanged for lower quality or used items. On the grandest scale it can be done by not implementing activities at all – creating fake receipts for training sessions that never happened or bridges that were never built.

Checking that activities were implemented needs to go beyond just checking that participant lists were signed and reports submitted (these are easy to fake as well). You actually need to randomly choose some participants and do an audit by contacting them and asking what they received. For equipment this means actually seeing the equipment and it’s quality. For construction works it means actually inspecting what was built. For extra tips see our article on how to use technology to monitor field activities.

Download Delivery Audit template

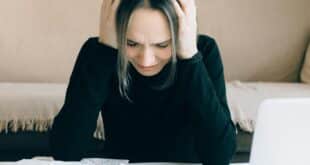

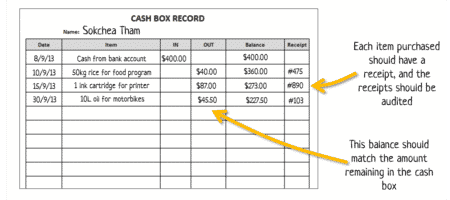

Have a stock and cash control system

The final, and most obvious, way to steal aid money is by direct theft of cash or supplies. This can either be done at the office or in the field, by staff or participants. To reduce the risk of theft it’s best to keep supplies and cash locked away, and to have a control system for them. The most simple type of control system is a record sheet like the ones shown below:

For supplies this means that all supplies going in or out of the store room are recorded, with the signature of the person doing this. For cash it means that each employee carrying cash must record all the cash they received in, and everything they paid out, with a corresponding receipt.

Provide ways for employees to report fraud and corruption anonymously

The U4 report on corruption and fraud in international aid projects recommends that all projects have a method for employees to anonymously report fraud and corruption. This could be a hotline for larger projects, or a locked box for smaller projects. Of course, once you set it up you need to make sure it’s checked regularly and reports are investigated quickly.

I’ve seen every type of fraud and corruption described in this article first hand – including on projects that got a perfect external audit report. So if you think this can’t be happening on your project, think again. Implement these simple steps to help prevent fraud in international development.

See also 7 things you can do to help stop per diem abuse

Photo by watchsmart