Review Overview

Accuracy - 6

Ease of use - 7

Usefulness - 6

6.3

A simple subjective way of measuring changes in quality of life.

Improving people’s quality of life is the ultimate goal for many international development programs, even though it might not be stated as such. Having a high quality of life just means having a full and happy life. For example, programs to increase people’s income or health only do this so those people can lead happier lives.

But how can you measure whether someone’s overall quality of life has improved? One way is to use the Batteries Methodology developed by CAFOD. Although this method was developed for measuring the quality of life of people living with HIV, it can also be used to measure changes in the quality of life for other groups.

How does it work?

The Batteries Methodology is a “participatory” approach, which means that the participants in the program help to decide what they want to measure and how they want to measure it.

The process normally starts with participants from the program brainstorming what a high quality of life means to them. This could include things like having enough money, being healthy, being able to go to school, owning land, having friends and family, or being able to attend religious ceremonies. CAFOD has used this technique with children, in which the children were asked to draw pictures of themselves being happy and these were used to generate ideas.

After the brainstorming is completed, the participants work together with a facilitator to group their ideas into at least four “domains”, which are the key ingredients of happiness. The standard domains that CAFOD uses are:

- Health

- Psychosocial/spiritual

- Legal and human rights

- Livelihood security

You don’t have to use these domains. The program participants can come up with their own domains and words to describe them.

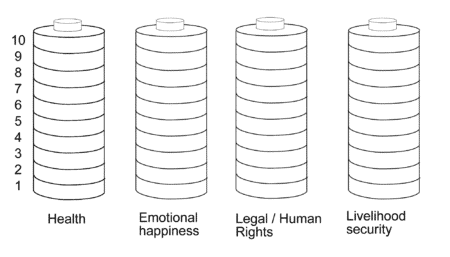

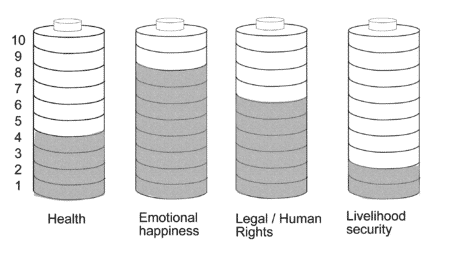

Once the domains are selected you then use them to create a set of batteries with a scale from 1 to 10 on the side. In the example below the program participants decided that “emotional happiness” was a better way to describe what they wanted to measure than “psychological / spiritual”, so this was used to label the battery. If participants have low literacy then you could use picture labels rather than text labels.

You then ask the program participants to shade in how full each of the batteries are for them personally. In the example below this individual feels that they have a high level of emotional happiness, but are low on the health and livelihood domains.

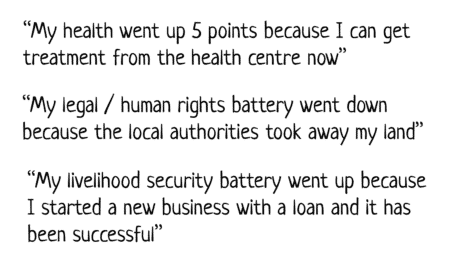

If you ask participants to rate how full their batteries are at two or more points in time you can measure the change in their scores. At each point they should record how the battery levels have changed, the reason for the change, the challenges they are facing, and their action plan. A useful template for doing this can be found in the CAFOD manual.

What is it like to use in practice?

I observed the Batteries Methodology being used by people living with HIV in Cambodia to measure changes in their quality of life. While it was a relatively simple process, we did run into a number of challenges.

Brainstorming the ingredients of happiness was easy enough. We asked people to draw pictures of themselves with a full and happy life, and we used them to create the domains, which ended up being quite similar to CAFOD’s standard domains. The only major problem we had during this step was agreeing on the names of the domains in both Khmer (the national language of Cambodia) and English. It was very difficult to find words that had exactly the same meaning in both languages.

The next challenge was explaining the batteries analogy to program participants. The picture of the batteries was not immediately obvious to them, and required quite a bit of explaining.

However, by far the biggest challenge was explaining what the numbers on the side of the batteries meant. The participants really wanted to know what each number represented. Did the number 1 in Health mean that you were dead or just really sick? Did the number 10 in livelihood security mean that you were a millionaire or just middle income?

Not having labels on the numbers made it difficult for people to decide how full their battery was. So if I was to do it again I would ask the group to brainstorm labels for the numbers 1 and 10 in each domain and agree on ones that made sense to them.

What do the results look like and how can they be used?

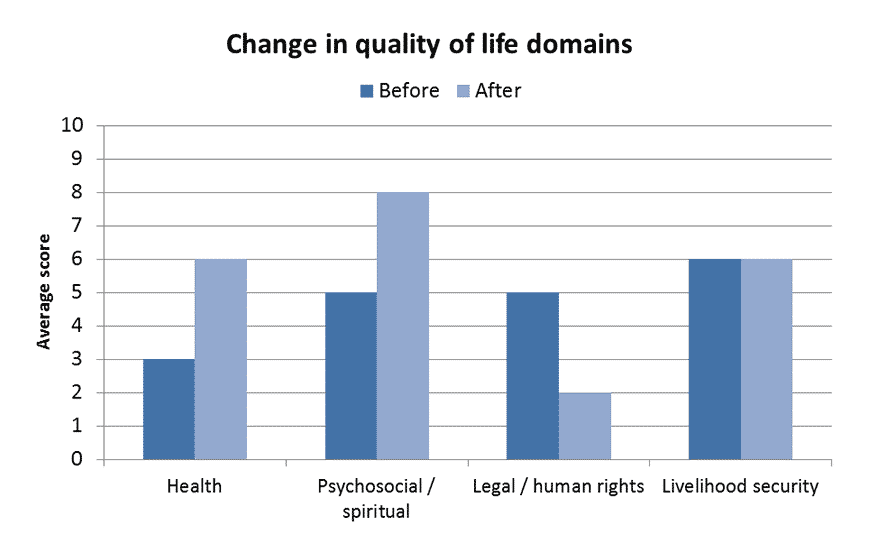

The Batteries Methodology creates two types of results. One is the change in scores across the domains. For example, if participants completed their batteries at the start and end of the program you could create something that looks like the chart below. From this chart you can see whether participants think that their quality of life is increasing or decreasing on average, and in which domains.

The second part of the results are the reasons why the changes occurred. These can be used as qualitative results to show why participants think that their quality of life increased or decreased.

What are the limitations?

The Batteries Methodology does have several limitations. Because participants decide which domains they want to measure, and what those domains mean, data collected in one program cannot be easily compared to another program.

When the numbers on the side of the battery aren’t labelled this also means that data collected from individual participants is subjective and can’t be compared directly. One person might think that number 1 in Health means they are dead, while another person might think that number 1 just means they are sick. So if they both gave a score of 5 that would mean different things to each participant.

There is also the problem of finding out what caused the change in scores. Because quality of life is so broad it is affected by many different things, which may or may not include the program you are running. So it’s difficult to know whether changes in the battery levels are actually the result of your program, or how you could improve your program to further improve people’s quality of life.

While the reasons that people give for the changes can help with this, my experience in Cambodia was that people don’t usually give detailed enough explanations of the change to be sure exactly what caused it. For example, they might say that “my livelihood score increased because my business is going well”. It isn’t clear from this statement whether the business going well has anything to do with the financial management training they received, or the microfinance loan they were offered.

The bottom line

The Batteries Methodology is one way to measure subjective changes in overall quality of life.

The Batteries Methodology is a good choice when:

- You want to involve program participants in creating the measurement tool.

- You want to know whether program participants think their own subjective quality of life has changed.

- Participants have low literacy.

The Batteries Methodology is NOT a good choice when:

- You want to measure changes in quality of life objectively.

- You need to compare quality of life between different groups or individuals on the same scale.

- You want to know whether the program actually caused the changes in quality of life.

Photo by Oxfam East Africa